Anyone who has been interested in politics for a reasonable length of time, or who sat through a college/university course in the humanities, has probably come across the term “neoliberalism.” You may have heard it referred to as the dominant economic model in the West since the conservative revolution of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. You also probably heard that the “neoliberal” model is in crisis right now and that it's responsible for just about every evil on earth, from the climate crisis to rising inequality.

You may also have noticed that those who denounce the phenomenon far outnumber those who use the word to describe their beliefs. This is a feature, not a bug! Indeed, the word is not used by the vast majority of market liberals (those accused of being neoliberals most of the time) for the simple reason that, since its inception, the term has been nothing but a convenient scapegoat for statists of all kinds.

Academic “explanations”

The most popular academic explanations of "neoliberalism" are, very often, complete nonsense. First, it is claimed that neoliberalism is the great return of economic liberalism as the dominant political and intellectual force, after the 70s and 80s. That is, following the abandonment of the Keynesian post-war consensus. Almost universally, it would then be said to have been an abject failure and blamed for just about any negative thing. This conception poses 3 major problems:

1. It's not true to say that, since the 70s and 80s, governments have been "neoliberal" (market-liberal) in every respect. Admittedly, several countries have removed trade barriers, privatized many state-owned companies, abolished price controls, and so on. On the other hand, public spending, and most notably social spending, have risen almost everywhere in the West, even if the pace of the increase has sometimes slowed. Despite what demagogues say, austerity has by no means been the norm over the past 40 years.

2. To the extent that major market reforms have been enacted, they have been highly successful. As a result, economies that had been steadily deteriorating have become competitive again, as we'll see a little further on. The idea that productivity and worker compensation have become detached from each other has been discredited numerous times. Openness to international trade has decimated extreme poverty worldwide at an unprecedented rate, and inequality in well-being and income between countries has fallen considerably (much to my dismay, the old myth of the zero-sum game still won't die). Contrary to popular belief, inequality has not risen significantly even within countries like the United States, when social transfers are properly accounted for. Even without considering social transfers, the wealth inequality is primarily driven by land/housing, a part of the economy that’s actually much more regulated today than prior to the 70s!

3. These market reforms weren't even driven by ideological motives most of the time. Frequently, they were initiated by left-wing governments who couldn't ignore the failure of the post-war social-democratic model and sought pragmatic solutions to revitalize it. For example, Jimmy Carter in the United States, Ingvar Carlsson in Sweden, Paul Keating and Bob Hawke in Australia, David Lange in New Zealand, James Callaghan in the UK and, a little later on, Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin in Canada, Fernando Henrique Cardoso in Brazil, Jens Stoltenberg in Norway, etc.

Another popular idea among many professors (especially in the humanities) is that “neoliberalism” is a corrupted version of liberalism, developed in parallel with the transition from classical to neoclassical economics. “Neoliberalism” is said to differ from the old liberal school by its deification of the market, its anthropological conception of a perfectly rational individual, its rejection of society and community, its belief in “trickle-down economics” and its desire to extend the concepts of economic efficiency and “commodification” to all spheres of human life. This second conception, particularly ridiculous, is purely a strawman. It's a vision that no free-market economist has ever defended, least of all those usually named as central figures of “neoliberalism” (e.g. Milton Friedman or Friedrich von Hayek).

One of the central arguments of market liberals is precisely that individuals are not perfectly rational, so it's better not to concentrate power in the hands of a small fraction of them, but rather let competition act as a process of “trial and error” in which individuals pay the real price for their bad decisions. When it comes to society and community, Robert Nisbet, a conservative-liberal sociologist, has noted in his magnum opus The Quest for Community that the rise of the welfare state was instrumental in breaking down social bonds, as responsibilities traditionally answered by local collectivities and mutual aid societies (see David T. Beito’s From Mutual Aid to the Welfare State) have been delegated to increasingly centralized and faceless government bureaucracies. The typical quote used to support this view of neoliberalism as an antisocial ideology is Thatcher’s notorious “there’s no such thing as society.” Forget about the fact that Thatcher has clarified her view many times, such as in the following passage of her second autobiography, a useful lie is often preferred to the truth:

[…] they never quoted the rest. I went on to say: There are individual men and women, and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people, and people must look to themselves first. It’s our duty to look after ourselves and then to look after our neighbour. My meaning, clear at the time but subsequently distorted beyond recognition, was that society was not an abstraction, separate from the men and women who composed it, but a living structure of individuals, families, neighbours and voluntary associations.

When it comes to “trickle-down economics,” Thomas Sowell dismantles the idea that the theory is truly what’s advocated by free-market economists in the following passage of Basic Economics: A Common Sense Guide to the Economy:

[…] any proposal by economists or others to cut tax rates, including reducing the tax rates on higher incomes or on capital gains, can lead to accusations that those making such proposals must believe that benefits should be given to the wealthy in general or to business in particular, in order that these benefits will eventually “trickle down” to the masses of ordinary people. But no recognized economist of any school of thought has ever had any such theory or made any such proposal. It is a straw man. It cannot be found in even the most voluminous and learned histories of economic theories. What is sought by those who advocate lower rates of taxation or other reductions of government’s role in the economy is not the transfer of existing wealth to higher income earners or businesses but the creation of additional wealth when businesses are less hampered by government controls or by increasing government appropriation of that additional wealth under steeply progressive taxation laws. Whatever the merits or demerits of this view, this is the argument that is made – and which is not confronted, but evaded, by talk of a non-existent “trickle-down” theory.

What the facts say

In his article titled The Unacknowledged Success of Neoliberalism, renowned economist Scott Sumner analyzes World Bank data on per capita income growth (in purchasing power parity) for several countries, from 1980 to 2008. In doing so, he notes that 4 countries performed better than the US and 2 countries performed similarly over this period. The 4 best-performing countries were Chile, the UK, Hong Kong and Singapore, and the 2 countries with similar performance were Australia and Japan. This analysis excludes poorer countries, as growth naturally slows down through diminishing marginal returns. It would therefore make for an unfair comparison. Let's take a closer look at what the best-performing economies from 1980 to 2008 have in common:

- Chile embarked on liberal economic reforms guided by the Chicago Boys during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, and even though the former was undoubtedly a bloodthirsty tyrant, this hasn't stopped the country's economy from prospering since. This period was dubbed the Chilean miracle, and is no myth.

- In 1979, Margaret Thatcher became British Prime Minister. At a time when the UK was considered “the sick man of Europe,” Thatcher undertook bold market liberal reforms that rapidly revitalized the British economy. Even the Labour Party, under Tony Blair, decided to maintain most of her reforms. Unfortunately, the British economy has not enjoyed similar prosperity since 2008, the end year of the data analyzed, as economic freedom slowly deteriorated.

- Even today, Hong Kong and Singapore generally dominate international economic freedom rankings (when included). Their virtually non-existent protectionist barriers and ridiculously low taxes have made these 2 city-states hotbeds of economic prosperity.

- Like the UK's, the US economy was not in good shape in 1980. Major “neoliberal” reforms have been undertaken, first by Jimmy Carter and then by Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton. In addition, the stagflation of the 1970s was countered by Paul Volcker, then head of the Federal Reserve, with monetary policies inspired by Milton Friedman's “neoliberal” monetarism (although Volcker and Friedman had their share of disagreements). As in the UK, economic freedom has unfortunately declined in the US since 2008.

- Australia is another example of a country that experienced economic difficulties in the 1970s. It was under a left-wing Labor government that moderate market liberal reforms were introduced in the 1980s. Conservative governments have then doubled down on their implementation, notably in the late 1990s.

- Japan has experienced the opposite trajectory to Australia. The Japanese economy was fairly free in the post-war period and remained prosperous until the 1990s. From the ‘90s to 2008, it deteriorated relative to the United States, as it became increasingly statist. Indeed, if the data stopped in the 1990s, Japan would have performed better than the US, rather than similarly.

Among the economies that regressed relative to the U.S. were Western countries that did not aggressively pursue market-liberal reforms during the period, such as France, Italy, Germany, and Switzerland. The last country may come as a surprise to many, as it has long had a very prosperous market-liberal economy. But, as Sumner notes, the statistics demonstrate exactly what one would expect from a free economy that hasn’t undergone any major market-liberal reforms since the 1980s: extraordinarily high wealth, but a decline relative to countries that have undergone such reforms during the same period.

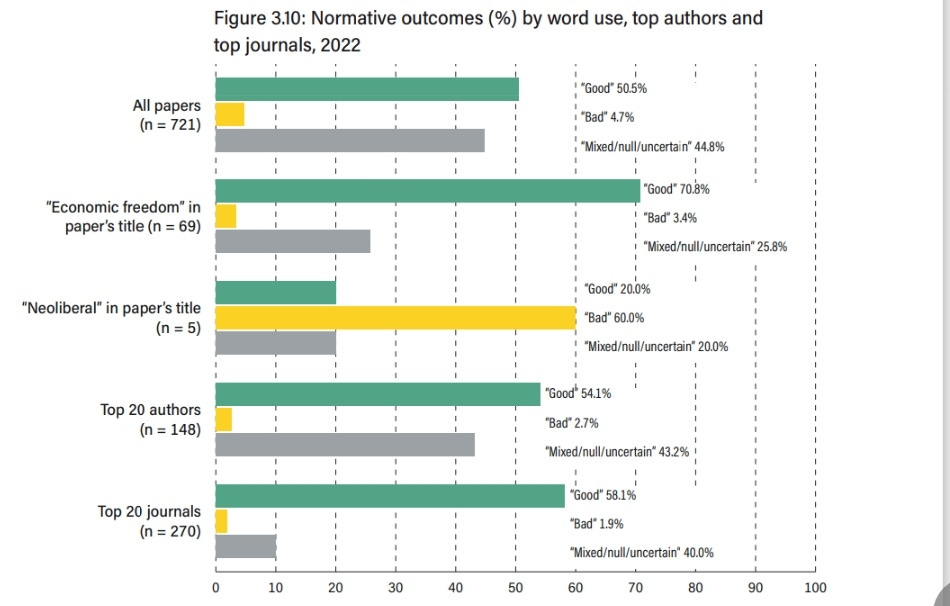

The Fraser Institute looked at more than 1,300 peer-reviewed journal articles citing its economic freedom index and found that more than 700 studied the impact of economic freedom on the human condition. Below are the normative outcomes of these papers, based on the variables analyzed:

Also, here’s how the studies’ normative outcomes varied with the use of “neoliberalism” in the paper’s title, if you still had any doubts concerning the pejorative nature of this descriptor:

What about the poorer countries that followed the so-called neoliberal recommendations of the Washington Consensus, a development strategy introduced mainly in the 1990s? Wouldn't it be fair to say that these failed, and that's why this development model is no longer dominant today?

A study by Kevin B. Grier and Robin M. Grier titled The Washington Consensus Works: Causal effects of reform, 1970-2015, demonstrates precisely the opposite. Over the period from 1970 to 2015, the sustained economic reforms of the Washington Consensus radically increased real GDP per capita over a 5 to 10-year horizon, they reliably raised average wages, and countries with sustained reforms were 16% richer after a decade. The truth is that these reforms are often unpopular because they can hurt people's living standards in the short run, but their effectiveness in the medium to long run is well-documented. Since electoralism often wins over rational considerations, it has been largely abandoned.

What about social mobility? Isn’t it true that this "neoliberalism" really only benefits the richest, that the additional growth ends up almost entirely in their pockets?

This is a question that Justin Callais, Vincent Geloso, and Alicia Plemmons attempted to answer in their study called Intergenerational Mobility, Social Capital, and Economic Freedom. Their analysis reveals the following:

[…] economic freedom almost always has an impact on absolute and relative mobility. While the literature is already clear that economic freedom increases income, this study is the first in the U.S. to show that the effects of economic freedom help those at the bottom more than those at the top. Social capital (more precisely, 'economic connectivity') also plays a role in mobility, but to a lesser extent than economic freedom. A person born in the freest quartile of American metropolises experiences 5-12% greater intergenerational income mobility than someone born in the least free quartile.

The pejorative origins of the term

Philip W. Magness, economic historian and Director of Research and Education at the American Institute for Economic Research, explores the origins of the descriptor in Why I am Not a Neoliberal. Magness shows that the first uses of the term came, not surprisingly, from Marxist thinkers. Specifically, German Marxists such as Max Adler and Alfred Meusel, in the early 1920s. It was then used to pejoratively describe the attempt by marginalists, notably of the Austrian economic school, to refute Karl Marx's critique of capitalism by attacking the labor theory of value and introducing the subjective theory of value instead. A few years later, the German fascists and Nazis adopted the term in their turn, again with the pejorative connotation that German Marxists had attributed to it. “Neoliberalism” represented a threat to their worldview because the so-called neoliberals defended methodological individualism, in stark opposition to their ultra-nationalism. Indeed, the fascist and national-socialist projects involved the subjugation of the individual to the collective interest of the nation.

For obvious reasons, the German Nazis' criticisms of "neoliberalism" did not enjoy great success after the Second World War. For its part, the far-left critique continued to be employed sparsely in left-wing academic literature. The subjective theory of value introduced by the marginalists was always associated with it. However, it wasn't until the mid-1980s that the descriptor became truly popular, with its "rediscovery" by Michel Foucault. From then on, the term took on more or less its current form, without ever losing its intrinsically pejorative nature.

Milton Friedman's famous article

Many neoliberal truthers refer to Milton Friedman’s article titled Neo-liberalism and its Prospects, published in 1951. In it, Friedman describes a new economic approach he finds interesting and states that the neo-liberal descriptor has sometimes been used to refer to. He goes on to name economist Henry Simons as its leading exponent. Here, we come closer to a real ideological movement. However, it resembles modern German ordoliberalism much more than the widespread academic caricatures called “neoliberalism,” emphasizing competition and order in the face of the supposed vagaries of the market.

Furthermore, Simons' vision was in no way shared by Hayek, who’s constantly referred to as one of the 2 most influential neoliberal theorists, along with Milton Friedman. Indeed, whereas Hayek advocated competition between several currencies as his ideal monetary policy, Simons advocated total state control of money. Moreover, Friedman's article is the only time he speaks of this “neo-liberalism,” and he then distanced himself strongly from Simons' proposals in his later years. We’re in no way talking about superfluous differences, but fundamental fractures. Until his very last breath, Friedman described himself as a resolute classical liberal, not a neoliberal. Ultimately, the article in question, far from influencing a new era of “neo-liberal” economists, went virtually unnoticed for almost half a century after its publication, as Magness demonstrates in his research.

To sum it up, hearing this term should immediately tell you that the person you’re talking to is probably possessed by ideology and knows nothing of the economic theories he’s criticizing. The best thing to do is to ask him which historical economist has identified with the descriptor a single time without repudiating it later in his career due to fundamental disagreements. Asking him to explain the difference between “neoliberalism” and economic liberalism is another simple way to reveal the vacuity of his remarks.

Hell, you could even send him this article!

So far, everyone I've known to use the word other than to mock it (myself, mostly) very clearly did not know what they were talking about, and what they did know was wholly derivative and unconsidered.

Great article as always! I actually started my first semester of college last fall, and one of my required classes was all about “power and privilege”. Even though our professor was quite accepting of the more right-leaning views of me and a couple other classmates, many of the assigned readings had some anti-capitalist undertones.